The History of Motor Vehicle Safety & Regulatory Laws

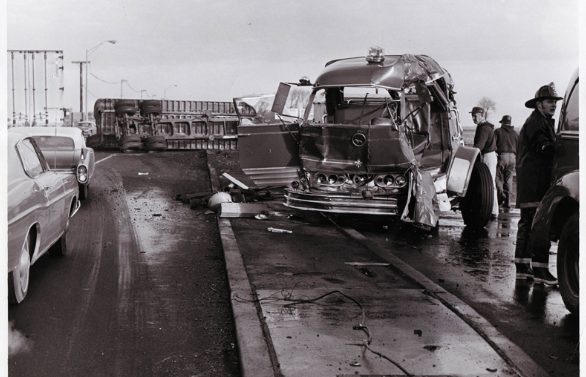

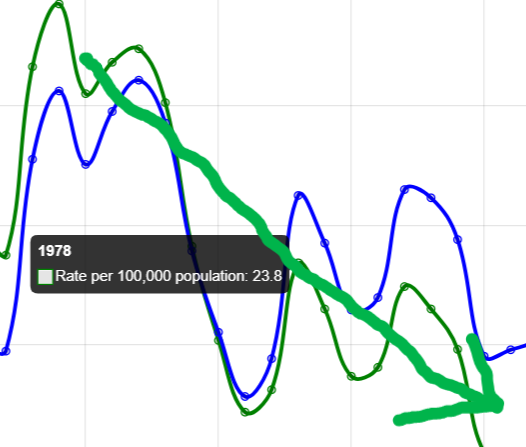

An average driver pulling out of their driveway in the 1950’s and 60’s had to stomach a lot of danger, as the average number of people per 100,000 who died from motor vehicle related accidents from 1950 to 1965 was 22.74. Even though part of American dream at the time was to be able to cruise around in a new fancy car, (and still is) regards for safety were not let's say, put first, as they are now. When Ralph Nader published his book in 1965, Unsafe at Any Speed, he meticulously brought to light many safety issues and malpractice within the industry, which came in the form of the Chevy Corvair primarily. He filed a lawsuit against General Motors, in which he used his research and knowledge in the book to help set a precedence and public understanding that manufacturers were often overlooking safety because it didn’t sell. Although the companies at the time were just playing to the consumers uninformed decisions, by designing good looking, fun cars, the Corvair along with other cars proved to be a breaking point, Nader wrote, "At the New York International automobile show April 7th 1965, their unprecedented action was the measure of their desperation over the inaction of the men and institutions in the government and industry who have failed to provide the public with the vehicle safety to which it is entitled" (Nader, 1965). Eventually the outcry and awareness of the public had a legislative effect, catching the attention of some higher up as a very pressing issue, On September 9th, at the signing of the 1966 vehicle and highway safety, President Lyndon B. Johnson told them that nearly three times as many Americans had died in traffic accidents in the 20th century as died “in all our wars.”. in the coming years various safety acts were passed to fight for the cause. Serious noticeable change was not seen for years though, as the average deaths were higher than before at 26.73 per 100,000 people on average from 1965-1973. As I go through a couple acts passed that were pivotal in the safety law history, I will also attempt to analyze to what extent they were effective or efficient. This historical review should serve adequate to my argument, but not as an all-inclusive history of traffic safety, thus I will be focusing on a little on the blunder of the interstate system overall and specifically the legislative blunder of a response.

Motor Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act

This act helped fund Traffic/accident investigation and proactive safety research because before this it had been a joke.

Ralph Nader: A Consumers Hero

When Ralph published his bestselling book, he filed a lawsuit against GM the next year, as he already pretty much had his case built. The outcomes of the case ultimately only furthered the public’s opinion and Nader’s influence as a tireless hero of law. His work also set the stage for future work that would pretense the vast web of bureaucracy and auto industry today.

DOT Established

Accident investigation, and implementation and enforcement of safety regulation established in the ACT in September

Impact of the DOT

Modern Context:

The Department of Transportation was extremely beneficial to conducting data collection and implemented accident investigation.

Highway Safety Act

Renaming the NHSD to NHSTA, which was headed with improving highway safety specifically. Among other efforts, this act made it federal law that states must create comprehensive highway safety plans.

Impact on Fatality

Even though Ralph had emphasized the importance of safety, it took 2 years before real change was implemented such as requiring manufacturing of seatbelts in cars after 1968. While late, the impact was still felt as the 1966 act as well as this revision in 1970 were actually amazing for the period, as this act added things like guardrails and other highway safety based on the research conducted. Much of this change took a while to be felt, but the death rates from 1968 decreased by about 5 per 100,000 people by 1978, when you look over the sudden decrease because of the energy crisis.

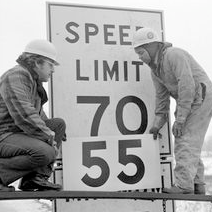

Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act

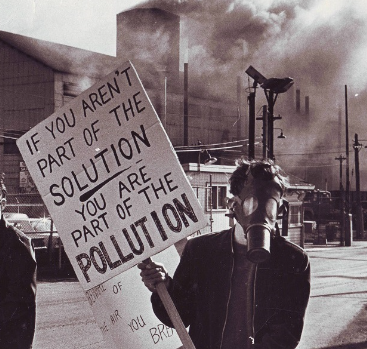

This was part of the energy crisis, under the idea that a 55mph federal limit would cause a decrease in fuel usage and it did! This act had included many other changes but primarily they combatted pollution.

Impacts of the Clean Air Act

Although the initial idea was for the speed limit to help gas consumption, and was after the clean air act nationally speaking; the largest impact was felt in pollution by automobiles, as well as cleaner air and fuel. Another large unintentional impact was the safety improvements, as the typical driver saw a less gruesome crash at 55mph.

NHSTA crash testing and front impact rating

Further research effort toward safety, actual measurable effects and data was implemented in manufacturing and design. Along with the actual establishment of NCAP.

Smart dummy?

It took 8 years to implement after it was originally in the 1970 safety act, which played a large part in the perceived inefficiency because there is often a noticeable lag in the fatality data, but there was also lag in the safety data. Also the numbers don’t immediately fall off after signing paper. Many of the safety-based design changes in average cars at the time were not impacted by this overnight, as 20 years later in 1998 much about car had changed but we had the data long before.

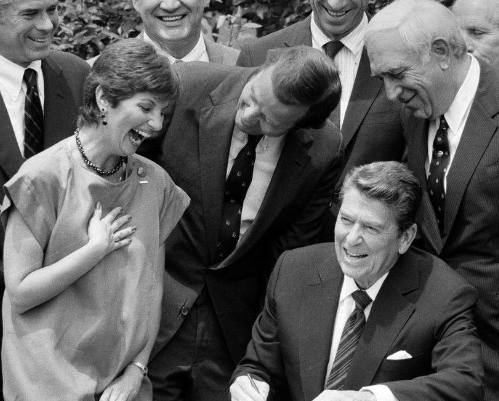

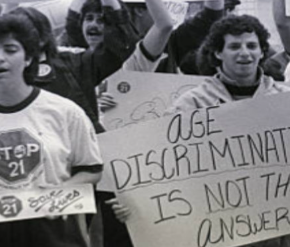

National Drinking age Act

While the Drinking Age Act didn't specifically reference drunk driving, it was a step in the right direction because the idea was frowned upon because of the times, as drinking was a large part of culture and still is. The idea was young and drunk is bad for driving, but this put a foot in the door that was later all drunk driving (>.08) is bad therefore illegal.

Effectiveness and implementation

The rhetoric before the sweeping changes and public outcry was that there was a nut behind the wheel, either drunk, high, or stupid, they were the explanation/scapegoat for the stupendously high death count. Americans had to fight themselves, as they wanted safety, but still were against the alcohol laws with an argument of freedom. Obviously, this is the right moral decision, but this was the first issue that hints at the issues in transportation conceptually, when the entire economy depends on driving and the average person must drive to survive; some people are going to drink and drive.

Intermodal Surface Efficiency Act

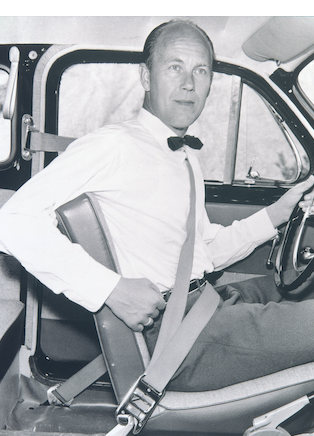

The air bag invention by John Hetrick’s in 1953 was an early pretense to the Act of 1991 that finally went into effect September 1, 1998–45 years after the idea was proposed and 7 years after the paper was signed even though seatbelt's positive impacts on safety were agreed. The law requires that all cars and light trucks sold in the U.S. have air bags on both sides of the front seat.

Public and Safety Impact

This law, similar to the drinking act, had public backlash because of this idea of individual freedom that is bestowed in every American. Although many wore their seatbelts who were smart enough to see the benefit, as it was not required to be worn until 1998, but cars had been required to be manufactured with a safety belt in 1968 as part of the effects of the safety act.

What does it all mean?

What stands out to me initially when viewing the data associated is that it seems that the public ideology is against the most effective parts of accident prevention in the first place, such as seat belts, drunk driving laws, speed, and this is still relevant today as in my personal experience many young friends of mine pertain to actions with a blatant disregard for their own personal safety. While I’m not going to go in depth to the psychology behind this because that could be its own paper, I will consider an example using my own bias that may explain these implementation issues. As a young, stupid, dangerous teenager, I enjoy speeding on the same freedom crux as people before me, and if a law were passed requiring say AI driving on the freeway/highway I would be against it for the same reasons, although in this theoretical law AI driving may be safer. Even though I am educated enough to understand the most effective action against crashes is preemptive, such as speeding, seatbelts, drinking, car design, and ultimately high-level autonomous driving, there is still a human aspect to implementation and enforcement. Further connecting this to the historical background I just covered, we can see that there is a lag time from paper signing to actual fatality effects, the seatbelt being the greatest example, especially because the public was not totally on board from a control aspect. Though as I mentioned before, seatbelts were required as per regulation in 1973, which isn't too bad considering there was little regard for safety until 1966. What this proves is that we should focus on what we can easily control from an organized perspective, even though it is hard to work against rich companies who have profit incentives, lobbyists, etc., it is still easier than forcing every joe bob to wear a seatbelt. I have been made aware a phrase “good enough for government work” which had me thinking alot about how it applied to this topic, and I concluded that the government should have focused their legislative efforts into harsher regulations of safety, with funding incentives for states who adopt federal policy which would include a mandamus based system which would extend into Manufacturing process, but also provide some tax relief. This same thing should have been done for infrastructure, but instead of requiring adoption of federal .08 bac law it could have included new road requirements making it harder to crash and easier to drive, as well as expansion of public transportation. Still, there is going to be a rich asshole who just likes to drink and drive which is why we design our cars with protection in mind, crumpling in the front.

Call to Action

In the future, as transportation needs, cars, and society change, we must make sure we are scrutinizing government actions when they are not good enough, especially regarding physical safety on the road but this speaks to other examples as well. The public is entitled to certain things, and as technology changes we must stay proactive in demanding certain minimums; we may not all agree on every detail of each issue, but often we agree that it is an issue, and less often, but still often, we also agree on part of the ideal outcome, all I'm suggesting is that we figure out what changes are easiest to implement nationwide that will have a significant impact at attaining a soft, temporary goal. To give one example as to credit my rambling, we could look at AI driving: Traffic crashes are economically and environmentally taxing, so we all agree that reducing that is good from an efficiency standpoint, but there are not enough crashes to justify requiring all driving automated. While we may reach a public interest economically, and privately, one day for this goal, many enjoy driving, but those who don’t enjoy driving often would benefit from not owning a car and relying on public transportation such as countries in Europe. Eventually, this will be revisited when an autonomous system of personal transport is more achievable, and the potential efficiency benefits in speed negate the cost, but annually, the total cost of crashes will probably hover around 500-billion-dollar range, because safety, insurance, cops, repair, maintenance, road conditions all will improve even as more people get on the road or one generation of crazy drivers inflates the numbers, etc. My final point is that the ineffective actions in the past, have large negative effect today, as we will continue to trail behind other countries in this aspect probably until all driving is automated. So be angry at the government when you hit a pothole and remember, the autobahn doesn’t have those.

Citations

United States, Congress. "National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966." Public Law 89-563, 89th Congress, 15 Oct. 1966. United States Statutes at Large, vol. 80, pp. 718-783.

"Traffic/accident investigation and proactive safety research. For carrying out section 402 of title 23, United States Code (relating to highway safety programs) by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, $75,000,000 for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1972, and $100,000,000 for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1973".

"Noncompliance, sec. 111. (a) If motor vehicle or item of motor vehicle equipment is determined not to conform to applicable Federal motor vehicle safety standards, or contains a defect which relates to motor vehicle safety, after the sale of such vehicle or item of equipment by a manufacturer or a distributor to a distributor or a dealer and prior to the sale of such vehicle or item of equipment by such distributor or dealer: (2) In the case of motor vehicles, the manufacturer or distributor, as the case may be, at his own expense, shall immediately furnish the purchasing distributor or dealer the required conforming part or parts or equipment for installation by the distributor or dealer on or in such vehicle and for the installation involved the manufacturer shall reimburse such distributor or dealer for the reasonable value of such installation plus a reasonable reimbursement of nonconformance to the date such vehicle is brought into conformance with applicable Federal standards".

"There is hereby established within the Department a National Transportation Safety Board (referred to hereafter in this Act as 'Board'). (b) There are hereby transferred to, and it shall be the duty of the duties. Board to exercise, the functions, powers, and duties transferred to the Secretary by sections 6 and 8 of this Act with regard to— (1) determining the cause or probable cause of transportation accidents and reporting the facts, conditions, and circumstances relating to such accidents".

United States, Congress. "Highway Safety Act of 1970." Public Law 91-605, 91st Congress, 31 Dec. 1970. United States Statutes at Large, vol. 84, pp. 1713-1772.

"The Secretary shall carry out through the Federal Highway Administration those provisions of the Highway Safety Act of 1966 (including chapter 4 of title 23, United States Code) for highway safety programs, research, and development relating to highway design, construction and maintenance, traffic control devices, identification and surveillance of accident locations, and highway-related aspects of pedestrian safety".

United States, Congress. "Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act of 1974." Public Law 93-239, 93rd Congress, 2 Jan. 1974. United States Statutes at Large, vol. 87, pp. 1046-1049.

"The Secretary of Transportation shall not approve any project under section 106 of title 23 of the United States Code in any State which has (1) a maximum speed limit on any public highway within its jurisdiction in excess of 55 miles per hour".

United States, Congress. "National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984." Public Law 98-363, 98th Congress, 17 July 1984. United States Statutes at Large, vol. 98, pp. 435-438.

"Prohibits the Secretary of Transportation from approving Federal-aid highway projects in States in which the purchase or public possession of alcoholic beverages by persons less than 21 years of age is lawful".

United States, Congress. "Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991." Public Law 102-240, 102nd Congress, 18 Dec. 1991. United States Statutes at Large, vol. 105, pp. 1914-2348.

Directs the Secretary to: (1) promulgate, by September 1, 1993, an amendment to Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard 208 in a number of ways, including requiring the installation of an airbag that meets the requirements of such Standard on both the driver and front outboard passenger seating positions of passenger cars and MPVs and other light trucks; and (2) require, after the promulgation of such amendment, that owner's manuals contain specific language informing consumers about the need to wear seatbelts even in vehicles equipped with airbags.

Authorizes appropriations for NHTSA highway safety programs, NHTSA highway safety R&D, and the alcohol traffic safety incentive grant program.

National Safety Council. "Deaths and Rates." Injury Facts, Accessed 1 June 2024.

"Nearly three times as many Americans had died in traffic accidents in the 20th century as died “in all our wars.” Auto accidents were “the biggest cause of death and injury among Americans under 35. And if our accident rate continues, one out of every two Americans can look forward to being injured by a car during his lifetime – one out of every two!” -President Lyndon B. Johnson, 1966.

Nader, Ralph. "At the New York International automobile show April 7th 1965, their unprecedented action was the measure of their desperation over the inaction of the men and institutions in the government and industry who have failed to provide the public with the vehicle safety to which it is entitled." Unsafe At Any Speed: The Designed-in Dangers of the American Automobile, preface, IX. Grossman Publishers, New York, 1965.